“Yves preferred to travel in his imagination; real places often disappointed him.”

Pierre Bergé

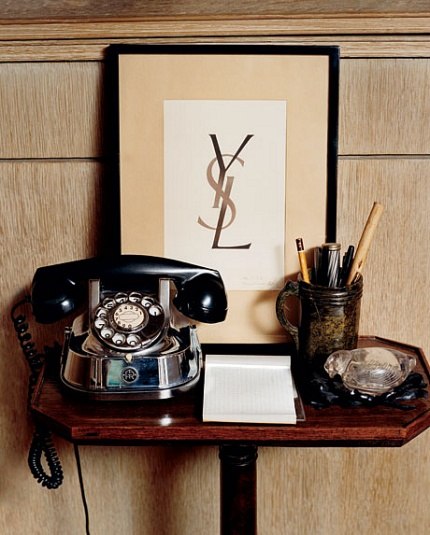

Stories like the following really get me upset. I still don’t understand why, treasures like these, end up to be auctioned and then dispersed. This fact happened in 2009, just an year after Yves Saint Laurent’s death. His partner Pierre Bergé, with whom he had a pacs (civil union), decided to put on sale the entire collection, except for the 1972 Andy Warhol portrait of Saint Laurent; a Senufo African bird sculpture, the first object that the two men purchased together; and the 1961 rendering of the YSL logo, by Cassandre.

Bergé and Saint Laurent met in 1958 and set themselves the goal of buying the best paintings and sculptures they could lay their hands on. In July 2008, Pierre Bergé announced that he would be selling their collection (amounting to some 800 lots) through Christie’s (in conjunction with his own auction house, Pierre Bergé & Associates). The decision to sell almost the whole collection was made by Bergé as a way to find closure. “I wanted this sale, this collection could only have two destinies: end up in a museum, which would have been too onerous, or on the auction block. I chose the sale because I felt the collection would not be truly complete until the hammer fell on the last lot. I hope that everything we loved so passionately will find a home with other collectors. That is the way with works of art,” Berge says, adding that he was selling “without regret and without nostalgia.”

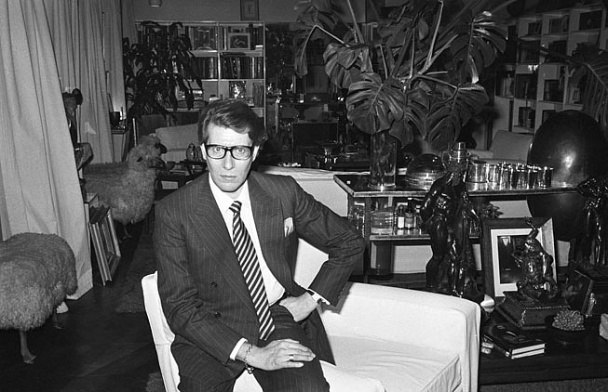

In 1969 Yves Saint Laurent and his partner, Pierre Bergé, came to inspect the apartment, until then, a vacated property. After a two-year restoration project, the couple settled in. Saint Laurent occupied the larger bedroom on the main floor, while Bergé installed himself in a smaller one, on the garden level. Among their early furnishings was a colossal late-19th-century West African wooden carving of a mythical bird: “I have a passion for objects depicting birds and snakes but in real life these animals scare me” said Saint Laurent. Another early acquisition was a pair of slick brass-and-lacquer Jean Dunand vases, originally exhibited in 1925 at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs. Though at this stage Saint Laurent was already an established star, he was by no means a rich man but he was able to understand the importance of Art Decò when nobody cares about. Infact when in November 1972 the Art Deco collections of Jacques Doucet were auctioned at Hôtel Drouot, in Paris, among the few farsighted bidders at the Doucet sale were Saint Laurent and Bergé. Doucet’s collection included paintings, like Picasso’s 1907 Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, as well as exotic oddities from such contemporary Deco artisans as Pierre Legrain, Eileen Gray, and Gustave Miklos.

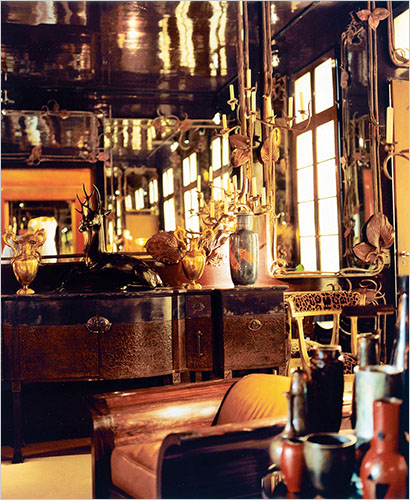

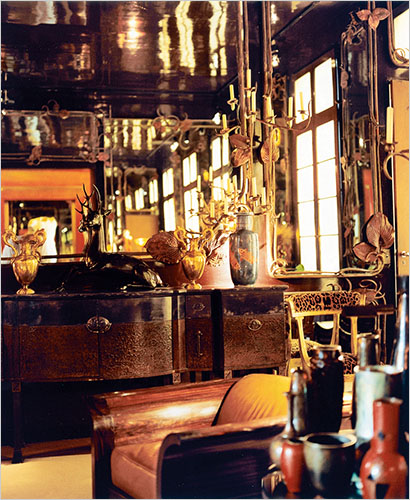

The sole other living visual artists whom Bergé and Saint Laurent patronized were François-Xavier and Claude Lalanne, the husband-and-wife sculptors. Claude Lalanne devised risqué body jewelry for Saint Laurent’s fall-winter 1969 line, and François-Xavier produced for Bergé and Saint Laurent’s library a lifelike flock of faux sheep. A pair of undulating lily-motif mirrors, crafted in bronze and copper by Claude Lalanne for the upstairs music room, led, between 1974 and 1985, to the proliferation of over a dozen more, floor to ceiling. “I can’t live in a room without mirrors,” Saint Laurent said. “If there aren’t any, the room is dead.” The effect in the music room of their multiplying reflections was vertiginous—a touch of Mad Ludwig of Bavaria, as seen through the lens of Luchino Visconti. “Some nights it’s a little unsettling,” Saint Laurent admitted.

The most influential figure for Saint Laurent tastes probably has been the iconoclastic Vicomtesse Marie-Laure de Noailles, whose wildly eclectic salon on the Place des États-Unis intoxicated the couturier to the point of delirium. Recalls decorator Jacques Grange, “Yves said that the salon of Marie-Laure de Noailles was the eighth wonder of the world”. An intimate of the Surrealists (her husband, Charles, had financed Buñuel and Dalí’s scandalous 1929 film, Un Chien Andalou) the vicomtesse was by the late 1960s a bizarre, nearly forgotten relic of the vanished world Saint Laurent worshipped.

Choosing paintings together was one of the strongest dialogues between Pierre and Yves. Each purchases were choosen by the couple together, to name a few: Madame L.R., a totem-like 1914–17 oak effigy of the Parisian hostess Léonie Ricou, by Constantin Brancusi, for about $500,000; Ingres’s early Portrait of the Countess de Larue, inscribed “Year XII”; a 1816–17 Géricault double portrait of the siblings Élisabeth and Alfred de Dreux; one of Matisse’s first colored-paper cutouts, The Dancer, from 1937–1938; Composition No. I, from 1920, in its original frame, by Piet Mondrian; the 1791 Goya likeness of the rosy-cheeked Don Luis María de Cistué y Martínez, from the Rockefeller collection (and later donated to the Louvre). By the late 80’s Bergé and Saint Laurent turned their acquisitive attentions instead to decorative objects like two Qing-dynasty bronze heads, of a rat and a rabbit. Designed by a Jesuit missionary, and previously owned by Misia Sert, these naturalistic animals once spouted water into the zodiac fountain of the Chinese emperor’s summer palace, pillaged by French and British soldiers in 1860 during the Second Opium War.

Bergé knew that Saint Laurent would not have approved of his plan to liquidate their collection. But, Bergé said “I don’t want to think about that. For a month, Yves had cancer and I had plenty of time to think. I decided to sell everything because the collection doesn’t exist if he doesn’t exist. After Yves’s death, to conserve the collection makes no sense. It will go away just like that. We all would very much like to attend our own funeral; of course, we can’t. But we can attend the funeral of a collection. It’s the end. It’s over. Economically, it’s impossible to do again. At my age, you don’t start a new collection, or buy wine too young, or plant small trees”. Bergé’s share of the profits will be divided between the Fondation Pierre Bergé–Yves Saint Laurent, dedicated to preserving the designer’s legacy, and a new foundation, which will be devoted to aids research.

Source: pictures and info vanityfair.com; nytimes.com; guardian.co.uk; parisbao.com; luxuo.com

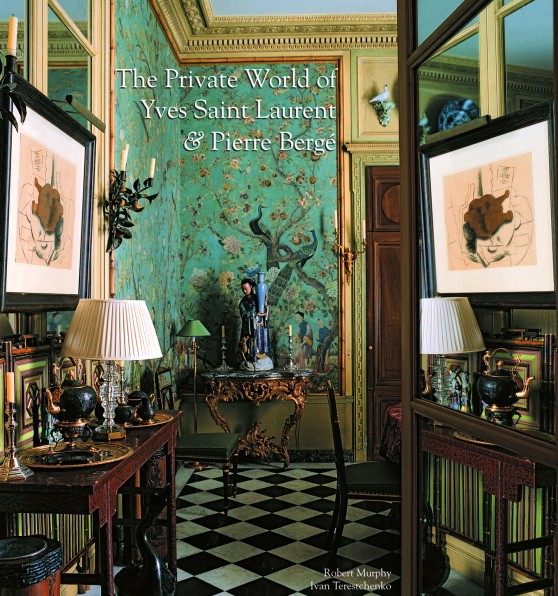

Today we can barely have an idea of what YSL’s home looked like thanks to the book “The Private World of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé” by Robert Murphy with photographs by Ivan Terestchenko. Focusing on the houses and collections of YSL and Pierre Bergé, the book features the eight residences that they had between them, including Rue de Babylone and Avenue de Breteuil (YSL residences), Rue Bonaparte (Bergé), and the pair’s homes in Deauville, Tangier, and Marrakech.

For more pictures of the book here.

Saint Laurent’s bedroom fireplace, with an Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann chair and a tabletop arrangement of precious bibelots, inspired by Vicomtesse Marie-Laure de Noailles.

Saint Laurent’s bedroom fireplace, with an Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann chair and a tabletop arrangement of precious bibelots, inspired by Vicomtesse Marie-Laure de Noailles.

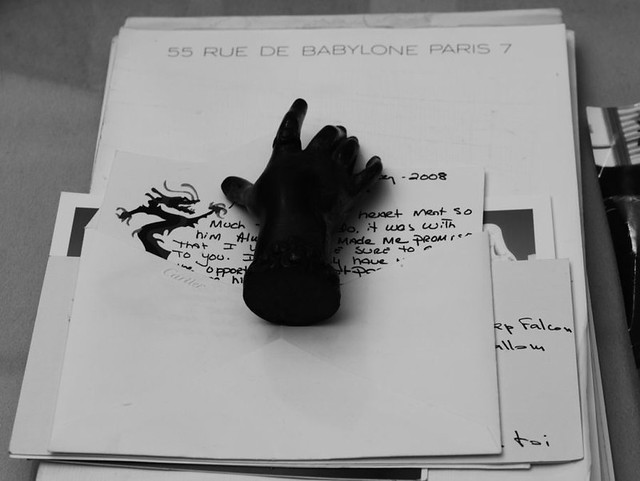

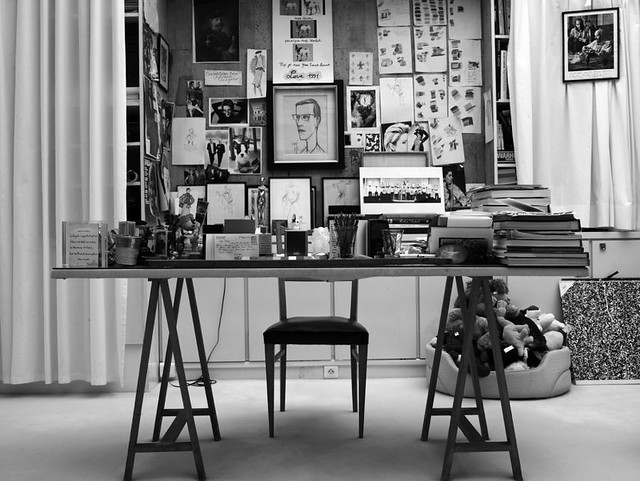

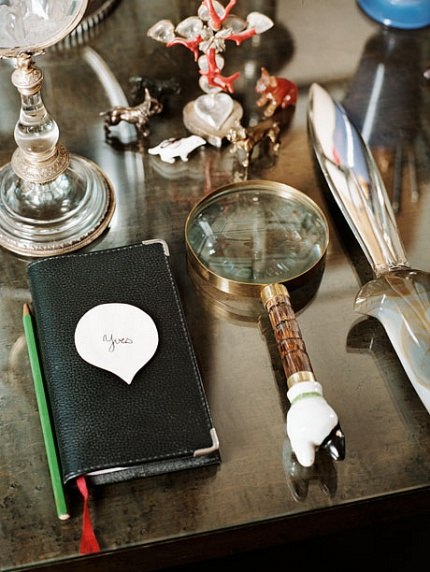

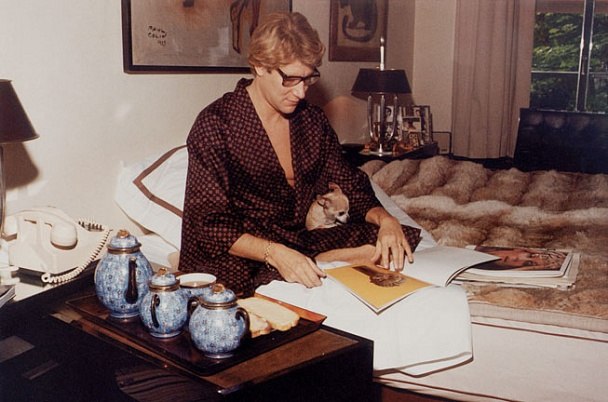

A desk in the bedroom, with a magnifying glass alongside a small leather-bound notebook with a notation “Yves” on the front cover.

“I have an affinity for louche decadence, which is one of the things on view here,” Pierson says. “There is a very opium-den quality — all those tables full of objects one can peruse in a haze.” The auction contains 733 lots, including a pair of second-century Roman busts and an entire room of Claude Lalanne bronze mirrors.

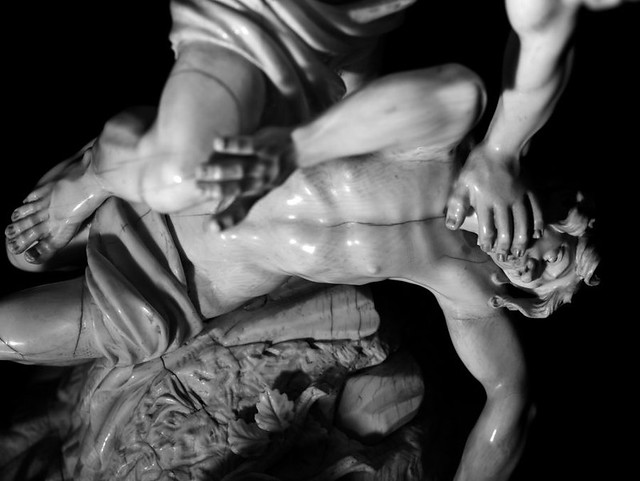

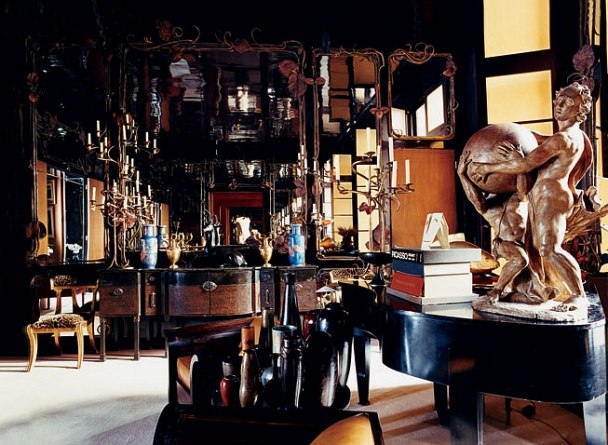

An ensemble of 15 Claude Lalanne mirrors, designed between 1974 and 1985, covers a wall in Saint Laurent’s Rue de Babylone music room, which also features an Eileen Gray chest, with an estimated value of $3.8 to $6.4 million. To the right, a 1707 terra-cotta Giovanni Antonio Rimondi sculpture is positioned on a piano.

An ensemble of 15 Claude Lalanne mirrors, designed between 1974 and 1985, covers a wall in Saint Laurent’s Rue de Babylone music room, which also features an Eileen Gray chest, with an estimated value of $3.8 to $6.4 million. To the right, a 1707 terra-cotta Giovanni Antonio Rimondi sculpture is positioned on a piano.

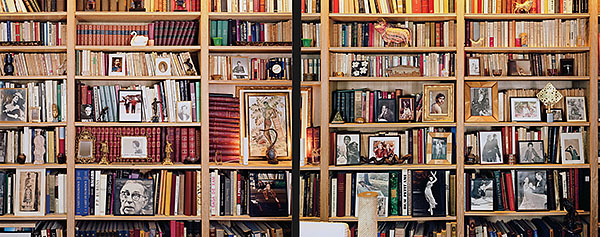

On a telephone table in the library of the Rue de Babylone apartment: the couture house’s original logo, hand-lettered by graphic artist Cassandre, from 1961 (not for sale). The bleached-oak bookcases are by Jacques Grange. Photograph by Pascal Chevallier

On a telephone table in the library of the Rue de Babylone apartment: the couture house’s original logo, hand-lettered by graphic artist Cassandre, from 1961 (not for sale). The bleached-oak bookcases are by Jacques Grange. Photograph by Pascal Chevallier

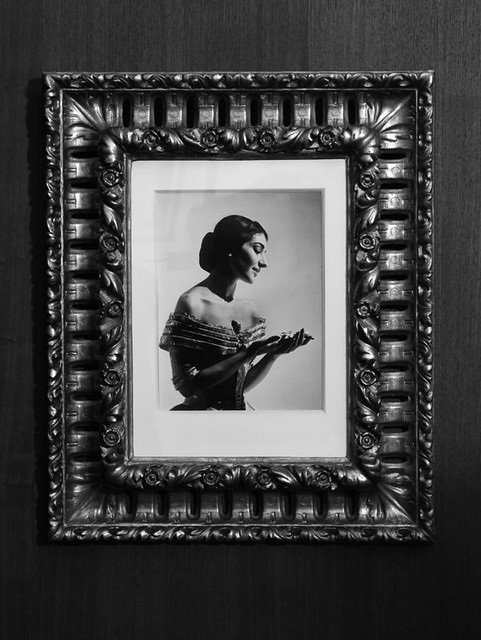

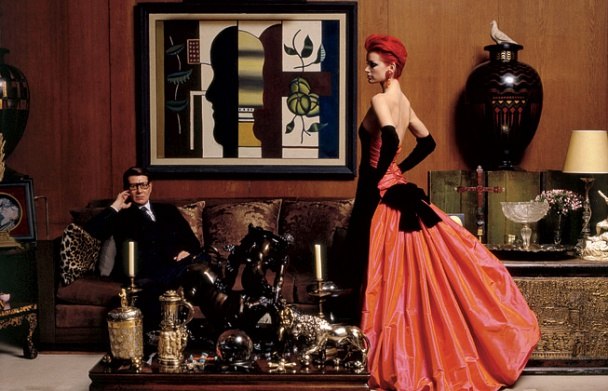

Yves Saint Laurent poses in the apartment’s grand salon for a November 1971 Vogue photo spread. Photograph by Horst P. Horst/courtesy of Condé Nast Archive.

Yves Saint Laurent poses in the apartment’s grand salon for a November 1971 Vogue photo spread. Photograph by Horst P. Horst/courtesy of Condé Nast Archive.

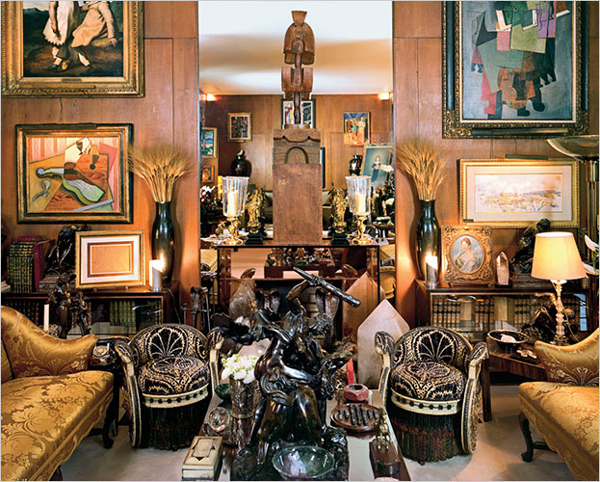

Butler Adil Debdoubi adjusts the Jacques Grange–designed curtains in Saint Laurent’s grand salon, which features artworks expected to fetch individually up to $50 million at auction: from left, the 1914–17 Brancusi wooden sculpture Madame L.R., a Gustave Miklos palmwood-and-red-lacquer stool, Picasso’s 1914 still life in oil and sand, Musical Instruments on a Table, above a late Cézanne watercolor of Mont Sainte-Victoire, an Eileen Gray circa 1920 dragon chair estimated at $4 to $6 million (in the foreground), Léger’s classicizing 1921 Cup of Tea (between the windows), and, at right, Vuillard’s circa 1891 Daydreaming Mary and Her Mother. Photograph by Pascal Chevallier

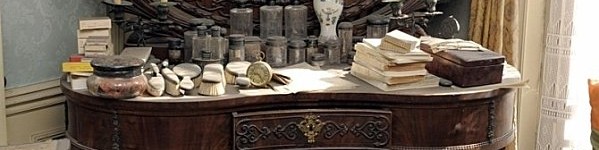

Bronze Qing-dynasty animal heads on either side of a fireplace mantle in Bergé’s Rue Bonaparte apartment.

A detail of the grand salon, where Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Portrait of the Countess de Larue (1812) is displayed to the right of one of two Gustave Miklos palmwood-and-red-lacquer benches, which are expected to auction for $2.5 to $3.8 million.

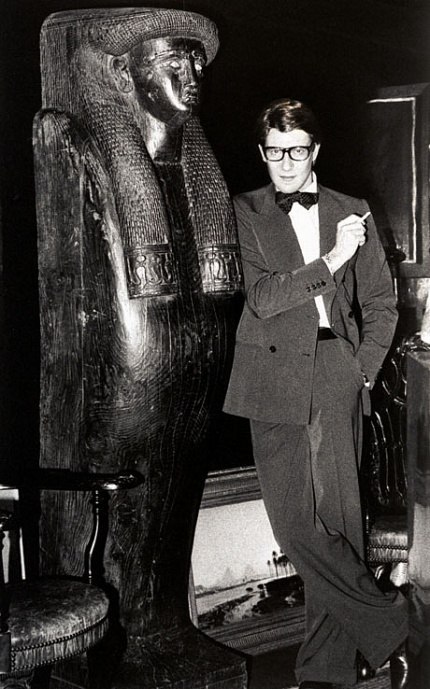

A Ptolemaic Egyptian sarcophagus stands between a pair of Louis XIII–era armchairs.

Photographed for Vogue’s January 1980 issue, the couturier leans against the sarcophagus in his Paris apartment. By Alexander Liberman/courtesy of Condé Nast Archive

Photographed for Vogue’s January 1980 issue, the couturier leans against the sarcophagus in his Paris apartment. By Alexander Liberman/courtesy of Condé Nast Archive

The contents of the apartment were arranged as if into a series of vignettes. Piet Mondrian’s “Composition Avec Grille 2,” one of five Mondrians owned by the designer, sits behind one of a pair of Armand-Albert Rateau table lamps. Saint Laurent liked symmetry. He said it calmed him.

“I had a profound feeling of the transience of life and the sheer audacity of our time here,” Vitali says. “There was not a single item that really stood out as such, but what did strike me, nonetheless, was the sheer abundance of contradictory objects: these contradictions are what life is made of.” The library shelves point to the breadth of the designer’s interests and inspirations. In the living room, the wood-paneled walls — and even the doors — were densely hung with works by Picasso, Léger and Gericault, just to name a few.

A 15th-century tapestry forms a backdrop to an Albert Cheuret Aloe lamp, circa 1925–30. To the right of the 18th-century Italian sofa hangs Théodore Géricault’s Portrait of Alfred and Elisabeth de Dreux (top), circa 1818, and Juan Gris’s 1913 The Violin (bottom), both estimated at $5 to $7.6 million. Photograph by Pascal Chevallier

Saint Laurent with a team of models showcasing looks from his fall 1972 collection. Courtesy of Condé Nast Archives

Saint Laurent with a team of models showcasing looks from his fall 1972 collection. Courtesy of Condé Nast Archives

Henri Matisse’s 1937–38 paper cutout The Dancer on a door in the library of the Rue de Babylone apartment.

In the library, a cylindrical crystal vase is situated on the François-Xavier Lalanne–designed multi-metal and ovoid Bar YSL. Mondrian’s 1920 Composition No. 1 is displayed above a fireplace.

Saint Laurent near the Bar YSL in the library, 1983. By Guy Marineau/courtesy of Condé Nast Archive

Saint Laurent near the Bar YSL in the library, 1983. By Guy Marineau/courtesy of Condé Nast Archive

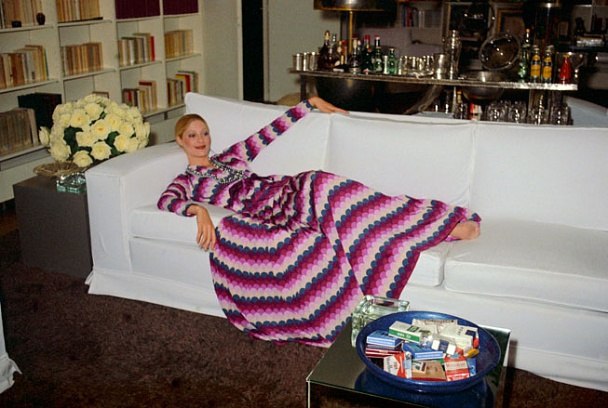

A model lounges in the library, wearing a gown from the YSL’s fall 1972 haute couture collection. By Reginald Gray/courtesy of Condé Nast Archive

Behind a 1920 Rateau leather armchair: Edvard Munch’s 1898 seascape hangs above Henri Matisse’s 1911 The Primroses, from the Blue and Pink Rug series. Below the two paintings is an Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann table lamp, circa 1927.

Exhibited on an easel, Francisco Goya’s Portrait of Don Luis Maria de Cistué (1791), which was donated to the Louvre Museum, is surrounded by a pair of cubic French Art Deco chairs and a Pierre Legrain stool, circa 1925. Toward the right is a 1925 Jean Dunand copper-and-enamel vase below a painting by Giorgio de Chirico, 1917–18

Yves Saint Laurent in the grand salon of his apartment on Rue de Babylone with model Sibyl Buck, October 27, 1995. They are surrounded by the Surrealist-period Léger painting The Black Profile (1928), sold by the artist’s widow, and Jean Dunand’s 1925 Art Deco brass-and-lacquer vase, among the treasures to be auctioned at the Grand Palais, in Paris, February 23 to 25. By Jean-Marie Perier/From Photos12/Polaris

Saint Laurent’s bedroom desk, with found-object Y’s alongside his trademark spectacles.

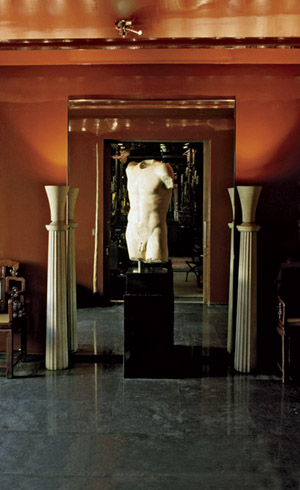

A first-century-A.D. Roman marble torso in the Grange-designed entrance hall of Saint Laurent’s apartment.

The designer at work in Paris, 1974. By Reginald Gray/courtesy of Condé Nast Archive

Saint Laurent’s French bulldog, Moujik, perched on a Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne 1974 Bird garden chair.

Saint Laurent’s French bulldog, Moujik, perched on a Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne 1974 Bird garden chair.

Hedi Slimane, now art director of Yves Saint Laurent, also took some pictures of the house. For more here.